RECRUITMENT

RECRUITMENT refers to the process of bringing together prospective employers and employees. The purpose of recruitment is to prepare an inventory of people who meet the criteria in job specifications so that the organisation may choose those who are found most suitable for the vacant positions.

Process of Recruitment:

The process begins by specifying the human resource requirements, initiating activities and actions to identify the possible sources from where they can be met, communicating the information about the jobs, terms and conditions and the prospects hey offer and encourage people who meet the requirements to respond to the invitation by applying for the job(s). Then the selection process begins with the initial screening of applications and applicants.

Job analysis would have already provided the job specifications i.e. qualities, qualifications, experience and abilities. Human Resource Planning provides the basis to arrive at the numbers, levels, and timing of recruitment.

Sources of Recruitment:

The requirement can be met from internal or external sources.

Internal Sources:

They include those who are employed in the organisation or those who were in the past employ (but quit voluntarily or due to retrenchment) and would return if the organisation likes to re-employ them. The advantage in looking for internal resources is that they provide opportunities for better deployment and utilisation of existing human resources through planned placements and transfers. It will also motivate people through planned promotions and career development when vacancies exist in higher grades. The law provides preferences to retrenched employees when vacancies arise in future.

External Sources:

Organisations may look for people outside it. Entry level jobs are usually filled by new entrants from outside. Also in the following circumstances organisations may resort to outside sources:

a. when suitably qualified people are not available.

b. when the organisation feels it necessary to impart new blood for fresh ideas.

c. when it is diversifying into new avenues and

d. when it is merging with another organisation.

RECRUITMENT refers to the process of bringing together prospective employers and employees. The purpose of recruitment is to prepare an inventory of people who meet the criteria in job specifications so that the organisation may choose those who are found most suitable for the vacant positions.

Process of Recruitment:

The process begins by specifying the human resource requirements, initiating activities and actions to identify the possible sources from where they can be met, communicating the information about the jobs, terms and conditions and the prospects hey offer and encourage people who meet the requirements to respond to the invitation by applying for the job(s). Then the selection process begins with the initial screening of applications and applicants.

Job analysis would have already provided the job specifications i.e. qualities, qualifications, experience and abilities. Human Resource Planning provides the basis to arrive at the numbers, levels, and timing of recruitment.

Sources of Recruitment:

The requirement can be met from internal or external sources.

Internal Sources:

They include those who are employed in the organisation or those who were in the past employ (but quit voluntarily or due to retrenchment) and would return if the organisation likes to re-employ them. The advantage in looking for internal resources is that they provide opportunities for better deployment and utilisation of existing human resources through planned placements and transfers. It will also motivate people through planned promotions and career development when vacancies exist in higher grades. The law provides preferences to retrenched employees when vacancies arise in future.

External Sources:

Organisations may look for people outside it. Entry level jobs are usually filled by new entrants from outside. Also in the following circumstances organisations may resort to outside sources:

a. when suitably qualified people are not available.

b. when the organisation feels it necessary to impart new blood for fresh ideas.

c. when it is diversifying into new avenues and

d. when it is merging with another organisation.

Internal Method:

This is filling up of vacancies from within through transfers and promotions. Transfer decisions are usually taken by the management and communicated to those concerned. In case of promotions, however, information about vacancies is communicated through internal advertisement or circulation and application are invited from eligible candidates who wish to be considered for the positions. Or the organisation may prepare seniority o seniority-cum-merit lists and consider the eligible candidates for internal promotions.

Some organisations keep a central pool of persons from which vacancies can be filled for manual jobs. Any person who remains on such rolls for 240 days or more is treated, in the eyes of law, as a permanent employee, and is therefore, entitled to all benefits including Provident Fund, Gratuity and retrenchment compensation under section 25F of the Industrial Disputes Act. Though the system appears to be costly, it has its own benefits, viz. (a) continuous supply of labour is assured (b) work is not affected due to absenteeism (c) there is no problem of fresh induction and (d) it is possible to train people in multi-skills.

Methods of Recruitment:

The methods of recruitment might include one or more of the following:

a. Direct

b. Indirect

c. Third-party.

Direct Method:

These include campus interviews and keeping a live register of job seekers. Usually used for jobs requiring technical or professional skills, organisations may visit IIT’s, IIM’s and colleges and universities and recruit persons for various jobs. Usually under this method, information about jobs and profile of persons available for jobs is exchanged and preliminary screening done. The short-listed candidates are then subjected to the remainder of the selection process.

Some organisations maintain live registers / records of job applicants and refer to them as and when the need arises. Usually in all such cases, preliminary screening is completed by examining the application form filled by the candidate and / or preliminary interviews.

Indirect Method:

These include advertisement in the print media, radio, T.V., trade, technical and professional magazines, etc. It is advisable to state in the advertisement the responsibilities and requirements along with definite hint about compensation, prospects etc.

This method is appropriate where there is plentiful supply of talent which is geographically or otherwise spread out and when the purpose of the organisation is to reach out to a larger group. However, it is not always possible to get key professionals or those with rare skills through this method.

Third-party Method:

They include reference to Employment Exchange, which is a statutory requirement for the jobs / organisations to which the Employment Exchanges (Compulsory Notification) Act applies. Special Employment Exchanges have been set up in different places for displaced persons, ex-military personnel, physically handicapped, professionals etc. For highly skilled technical jobs University Employment Bureaux and the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research have also been set up. There are many problems in developing such services efficiently and organisations successfully contested such rulings by filing cases in courts when they were asked to select only from among those sponsored by the employment exchanges.

Head Hunting services, consultancy firms, professional societies and temporary help agencies are among other sources of third-party recruitment. Traditionally, in India the following methods are used:

• Casual labour presenting itself at the factory gates on a day-to-day basis and offering themselves for employment

• Hiring through labour contractors, maistries etc.

• Spreading information about jobs through word of mouth including friends and relatives, present employees etc.

In recent times, new form of sub-contracting, franchising, home-work and contractual norms of work are emerging.

Some of the legal and political restraints limiting the sources of recruitment are mentioned briefly below:

1. Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation ) Act, 1986:

This Act replaces the Employment of Children Act, 138, and seeks to prohibit the engagement of children below 14 years of age in certain employment and to regulate the conditions of work of children in certain other employment. Penalties for contravening the provisions are fine and imprisonment.

2. The Employment Exchanges (Compulsory Notification of Vacancies) Act, 1959:

The Act requires all employers to notify vacancies (with certain exemptions) occurring in their establishments to the prescribed employment exchanges before they are filled. The Act covers al establishments in public sector and non-agricultural establishments employing 25 or more workers in the private sector. Employers are also required to furnish quarterly return in respect of their staff strength, vacancies and shortages and a biennial return showing occupational distribution of their employees. While notification of vacancies is compulsory, selection need not be confined only to those who are forwarded by the concerned Employment Exchanges.

3. The Apprentices Act, 1961: The Act seeks to provide for the regulation and control of training apprentices and for matters connected therewith. The Act provides for a machinery to lay down syllabi and prescribe period of training, reciprocal obligations for apprentices and employers etc. The responsibility for engagement of apprentices lies solely with the employer. An apprentice is not a workman.

4. The Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970:

This Act seeks to regulate the employment of contract labour in certain eablishments and to provide for the abolition in certain circumstances. The Act applies to every establishment / contractor employing 20 or more persons.

5. Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976:

This Act seeks to provide for the abolition of bonded labour system with a view to preventing the economic and physical exploitation of the weaker sections of society.

6. The Inter-state Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979: This Act safeguards the interests of the workmen who are recruited by contractors from one state for service in an establishment situated in another state and to guard against the exploitation of such workmen by the contractors.

7. The Factories Act, 1948, the Mines Act, 1952, etc. :

Certain legislation, like the Factories Act and the Mines Act prohibit employment of women (in night work, underground work etc.) and children (below 14 years of age) in certain types of jobs.

8. Reservations for Special Groups:

In pursuance of the constitutional provisions, statutory reservations and relaxed norms have been provided in education and employment to candidates belonging to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in central and state services including departmental undertakings, government corporations, local bodies and other quasi - government organisations. Most state governments have issued policy directives extending the reservations to notified backward communities also.

Over the years, the concept of reservations in education and employment has been extended to other categories as measures to tackle social problems or to pursue socio-political objectives. Such categories include: physically handicapped and disabled persons, women, ex-servicemen, sportspersons etc.

9. Sons -of -the-Soil:

The question of preference to local population in the matter of employment has become more complex toady than ever before. The National Commission on Labour suggested that the solution to the problem has to be sought in terms of the primacy of common citizenship, geographic and economic feasibility of locating industrial units on the one hand and the local aspirants on the other. The Govt. of India has recognised the main elements of the arguments on behalf of the sons of the soil and laid down certain principles in the matter of recruitment to its public sector projects, whose implementation, however, is left to the undertakings themselves.

10. Displaced Persons: Whenever major projects are set up, large tracts of land are acquired for the purpose, displacing several hundred households in each case. Payment of compensation for land was at one time considered a sufficient discharge of obligation towards persons who are dispossessed of land. This alone did not solve the question of earning livelihood.

Therefore, it is argued that young persons from families whose lands are acquired should be provided opportunity for training and for employment likely to be created in new units set up on these lands. The National Commission on Labour made certain recommendations.

a. Young persons from families whose lands are acquired for industrial use should be provided training programmes for employment likely to be created in new units set up on these lands.

This is filling up of vacancies from within through transfers and promotions. Transfer decisions are usually taken by the management and communicated to those concerned. In case of promotions, however, information about vacancies is communicated through internal advertisement or circulation and application are invited from eligible candidates who wish to be considered for the positions. Or the organisation may prepare seniority o seniority-cum-merit lists and consider the eligible candidates for internal promotions.

Some organisations keep a central pool of persons from which vacancies can be filled for manual jobs. Any person who remains on such rolls for 240 days or more is treated, in the eyes of law, as a permanent employee, and is therefore, entitled to all benefits including Provident Fund, Gratuity and retrenchment compensation under section 25F of the Industrial Disputes Act. Though the system appears to be costly, it has its own benefits, viz. (a) continuous supply of labour is assured (b) work is not affected due to absenteeism (c) there is no problem of fresh induction and (d) it is possible to train people in multi-skills.

Methods of Recruitment:

The methods of recruitment might include one or more of the following:

a. Direct

b. Indirect

c. Third-party.

Direct Method:

These include campus interviews and keeping a live register of job seekers. Usually used for jobs requiring technical or professional skills, organisations may visit IIT’s, IIM’s and colleges and universities and recruit persons for various jobs. Usually under this method, information about jobs and profile of persons available for jobs is exchanged and preliminary screening done. The short-listed candidates are then subjected to the remainder of the selection process.

Some organisations maintain live registers / records of job applicants and refer to them as and when the need arises. Usually in all such cases, preliminary screening is completed by examining the application form filled by the candidate and / or preliminary interviews.

Indirect Method:

These include advertisement in the print media, radio, T.V., trade, technical and professional magazines, etc. It is advisable to state in the advertisement the responsibilities and requirements along with definite hint about compensation, prospects etc.

This method is appropriate where there is plentiful supply of talent which is geographically or otherwise spread out and when the purpose of the organisation is to reach out to a larger group. However, it is not always possible to get key professionals or those with rare skills through this method.

Third-party Method:

They include reference to Employment Exchange, which is a statutory requirement for the jobs / organisations to which the Employment Exchanges (Compulsory Notification) Act applies. Special Employment Exchanges have been set up in different places for displaced persons, ex-military personnel, physically handicapped, professionals etc. For highly skilled technical jobs University Employment Bureaux and the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research have also been set up. There are many problems in developing such services efficiently and organisations successfully contested such rulings by filing cases in courts when they were asked to select only from among those sponsored by the employment exchanges.

Head Hunting services, consultancy firms, professional societies and temporary help agencies are among other sources of third-party recruitment. Traditionally, in India the following methods are used:

• Casual labour presenting itself at the factory gates on a day-to-day basis and offering themselves for employment

• Hiring through labour contractors, maistries etc.

• Spreading information about jobs through word of mouth including friends and relatives, present employees etc.

In recent times, new form of sub-contracting, franchising, home-work and contractual norms of work are emerging.

Some of the legal and political restraints limiting the sources of recruitment are mentioned briefly below:

1. Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation ) Act, 1986:

This Act replaces the Employment of Children Act, 138, and seeks to prohibit the engagement of children below 14 years of age in certain employment and to regulate the conditions of work of children in certain other employment. Penalties for contravening the provisions are fine and imprisonment.

2. The Employment Exchanges (Compulsory Notification of Vacancies) Act, 1959:

The Act requires all employers to notify vacancies (with certain exemptions) occurring in their establishments to the prescribed employment exchanges before they are filled. The Act covers al establishments in public sector and non-agricultural establishments employing 25 or more workers in the private sector. Employers are also required to furnish quarterly return in respect of their staff strength, vacancies and shortages and a biennial return showing occupational distribution of their employees. While notification of vacancies is compulsory, selection need not be confined only to those who are forwarded by the concerned Employment Exchanges.

3. The Apprentices Act, 1961: The Act seeks to provide for the regulation and control of training apprentices and for matters connected therewith. The Act provides for a machinery to lay down syllabi and prescribe period of training, reciprocal obligations for apprentices and employers etc. The responsibility for engagement of apprentices lies solely with the employer. An apprentice is not a workman.

4. The Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970:

This Act seeks to regulate the employment of contract labour in certain eablishments and to provide for the abolition in certain circumstances. The Act applies to every establishment / contractor employing 20 or more persons.

5. Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976:

This Act seeks to provide for the abolition of bonded labour system with a view to preventing the economic and physical exploitation of the weaker sections of society.

6. The Inter-state Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979: This Act safeguards the interests of the workmen who are recruited by contractors from one state for service in an establishment situated in another state and to guard against the exploitation of such workmen by the contractors.

7. The Factories Act, 1948, the Mines Act, 1952, etc. :

Certain legislation, like the Factories Act and the Mines Act prohibit employment of women (in night work, underground work etc.) and children (below 14 years of age) in certain types of jobs.

8. Reservations for Special Groups:

In pursuance of the constitutional provisions, statutory reservations and relaxed norms have been provided in education and employment to candidates belonging to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in central and state services including departmental undertakings, government corporations, local bodies and other quasi - government organisations. Most state governments have issued policy directives extending the reservations to notified backward communities also.

Over the years, the concept of reservations in education and employment has been extended to other categories as measures to tackle social problems or to pursue socio-political objectives. Such categories include: physically handicapped and disabled persons, women, ex-servicemen, sportspersons etc.

9. Sons -of -the-Soil:

The question of preference to local population in the matter of employment has become more complex toady than ever before. The National Commission on Labour suggested that the solution to the problem has to be sought in terms of the primacy of common citizenship, geographic and economic feasibility of locating industrial units on the one hand and the local aspirants on the other. The Govt. of India has recognised the main elements of the arguments on behalf of the sons of the soil and laid down certain principles in the matter of recruitment to its public sector projects, whose implementation, however, is left to the undertakings themselves.

10. Displaced Persons: Whenever major projects are set up, large tracts of land are acquired for the purpose, displacing several hundred households in each case. Payment of compensation for land was at one time considered a sufficient discharge of obligation towards persons who are dispossessed of land. This alone did not solve the question of earning livelihood.

Therefore, it is argued that young persons from families whose lands are acquired should be provided opportunity for training and for employment likely to be created in new units set up on these lands. The National Commission on Labour made certain recommendations.

a. Young persons from families whose lands are acquired for industrial use should be provided training programmes for employment likely to be created in new units set up on these lands.

To remove unjustified apprehension among local candidates, the following steps should be taken to supervise implementation of the Govt. of India directive on recruitment in public sector projects:

While recruiting unskilled employees, first preference should be given to persons displaced from the areas acquired for the project; and the next preference given to those who have been living in the vicinity.

ii. Selection of persons to posts in lower scales should not be left entirely to the head of the units. It should be through a recruitment committee with a nominee of the Govt. of the State within which the unit is located as a member of the committee.

iii. In the case of middle-level technicians where the recruitment has to be on an all-India basis, a member of the State Govt. should officiate on the Board of the Directors.

iv. Apart from the report sent to the concerned ministry at the Centre, the undertaking should send a statement to the State Govt. at regular intervals, preferably every quarter, about the latest employment and recruitment position.

Although the Commission has suggested these steps for employment in the public sector, they feel that the above should apply equally to recruitment in the private sector, though the mechanism to regulate recruitment in private sector will necessarily differ from that in public sector.

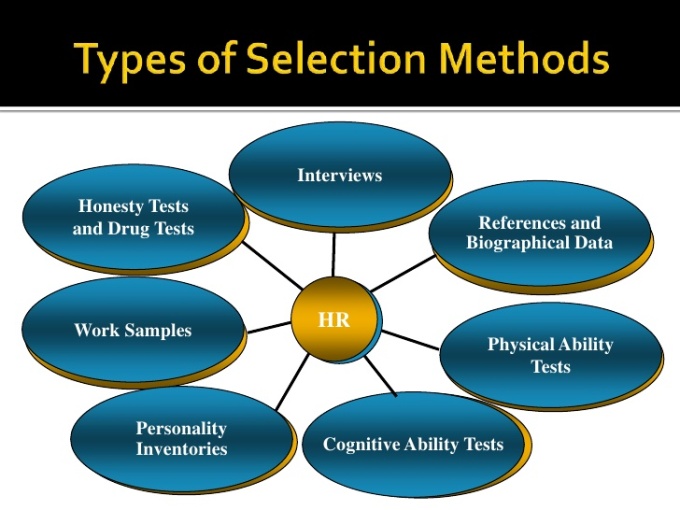

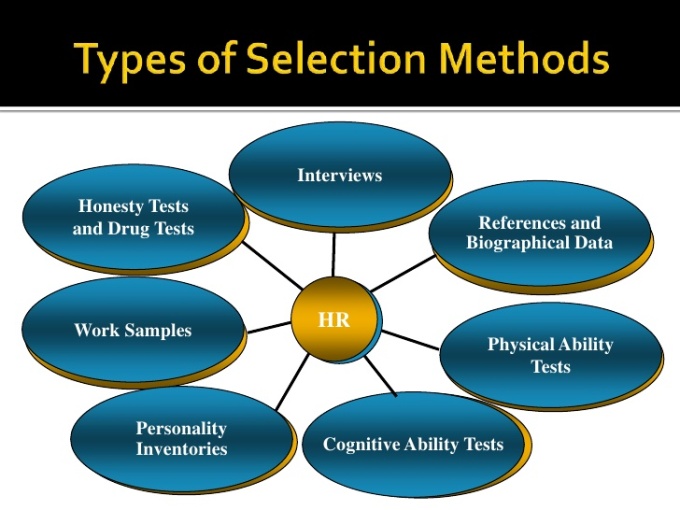

SELECTION:

Selection is a process of measurement, decision making and evaluation. The goal of a selection system is to bring in to the organisation individuals who will perform well on the job. A good selection system must also be fair to the minorities and other protected categories.

To have an accurate and fair selection system, an organisation must use reliable and valid measures of job applicant characteristics. In addition, a good selection system must include a means of combining information about applicant characteristics in a rational way and producing correct hire and no-hire decisions. A good personnel selection system should add to the overall effectiveness of the organisation.

Organisations vary in the complexity of their selection system. Some merely skim applications blanks and conduct brief, informal interviews, whereas others take to resting, repeated interviewing, background checks and so on. Although the latter system is more costly per applicant, many benefits are realised from careful, thorough selection. An organisation needs to have members who are both skilled and motivated to perform their roles. Either such members can be identified by careful selection or attempts can be made to develop them after hire by extensive training. Thus cursory selection may greatly increase training and monitoring costs, whereas spending more on the selection process will reduce these post-hire expenses.

Selecting the right people is also critical to the successful strategy implementation. The organisation’s strategy may affect job duties and design, and the job should drive election. For instance, if a company plans to compete on the basis of prompt, polite, personalised service, then service and communication skills should be featured in the job specification of the job analysts, and selection devices that can identify these skills in front-line applicants should be chosen. This argument is based on the assumption that the organisation’s strategy is clear, well known, and fairly stable so that people who fit the strategy can be selected.

Companies are beginning to realise that the foundation of their competitive strategy is the quality of their human capital. Having a top-notch, flexible, innovative staff may be a competitive advantage that is more sustainable than technical or marketing advantages. Such people will be able to generate and implement a wide range of new strategies in order to respond to quickly to a changing environment. This suggests hiring the best individual one can find, rather than hiring those who fit a specific job or strategy that exists today but may be gone tomorrow. “Best” in this new context means best in intelligence and best in interpersonal skills, as many jobs in rapidly changing organisations involve teamwork, negotiation, and relationship management.

The Process of Selection:

Most organisations use more than one selection device to gather information about applicants. Often these devices are used sequentially, in a multiple-hurdle decision-making scheme (candidates must do well on an earlier selection device to remain in the running and to be assessed by later devices).

Application Blank Reject Some Candidates

Screening Interview Reject Some Candidates

Tests Reject Some Candidates

More Interviews Reject Some Candidates

Reference Checks Reject Some Candidates

Conditional Offers Reject Some Candidates

Physical Examination

Hire

Often HR department takes the responsibility for the first few hurdles of assessing application blanks, conducting brief screening interviews, and administering ability tests. Then one or more managers / supervisors interview the survivors of these hurdles. Finally pending satisfactory reference checks, offers are made, medical examinations are completed and hiring is finalised.

Application Blanks and BIODATA: Application blank and / or resume is the first selection hurdle for most jobs. Application blanks request information about education, history and skills, as well as names and addressees of the applicant and several references. Most of the information requested is factual and can be verified, such as degrees earned or dates of employment. Application blank or resume fraud is not uncommon. Some studies indicate that 20 to 50 percent of the candidates falsify or slightly inflate some of their credentials.15 Thus seeking confirmation of important credentials is a wise practice.

Most organisations use application blanks or resumes to screen out candidates who do not meet the minimum job specifications on education or experience. Beyond these basics, a manager or HR officer may informally evaluate the application to find the candidates who look most promising. The criteria applied in making this judgement may not be explicit, job-related or consistent from one screener to the next.

A second way that organisation can use an application blank data is to apply a weighing scheme, in which only items known to relate to job success are scored and utilised in decision making. Weighted application blank (WAB) procedures have been shown to produce scores that predict performance, tenure and employee theft. Because the weights are valid and are applied consistently to all applicants, this method of using application blank data is more reliable than the informal evaluation.

Using Biodata, Experience, and Accomplishment Records for Selection: Biodata is a term used to refer to any type of personal history, experience, or education information. Some organisations use a biographical -information questionnaire instead of or in addition to, the usual application blank. These biodata questionnaires may be much more detailed than application blanks, and may be scored with keys based on very sophisticated statistical analyses.16. Sample questions might include “Do you repair mechanical things in your home, such as appliances?” “As a child, did you collect stamps?” Or “How many times did your family move while you were growing up?” One such biodata question – “Did you ever build a model aeroplane that flew?” -- was almost as powerful a predictor of success in flight training during World War II as the entire U.S. Air Force battery of selection tests. 17

Experience an Accomplishments Records:

Rather than relying on informal methods of evaluating candidate’s training, job-experience, and accomplishments, some organisations use content-valid-job-experience questionnaires to screen candidates for technical and professional jobs. The usual procedure is to conduct a job analysis by the task inventory method, in order to identify the most the most important or time-consuming tasks. The results of this job analysis are turned in to questions about the past work experience with each task or with each type of equipment used.

Applicants answer each task question by selecting one of the following responses:

▪ I have never done this task

▪ I have done it under supervision

▪ I have done it on my own

▪ I have supervised and / or taught this task

To discourage inflated self-ratings, the questionnaire may ask the applicants to list the names and addresses of people who can verify their experience with each task.

In addition, some job-experience questionnaires contain a few plausible sounding but non-existent task statements (such as typing from audio-FORTRAN reports, operating matriculation machines). Applicants who claim to have performed these non-existent tasks may be exaggerating their experience with real tasks.

Tests:

A test is a means of obtaining a standardised sample of behaviour. Tests are standardised in content, scoring, and administration. That is every time a test is given, its questions are identical or, in the case of tests with more than one form, equivalent. The scoring rules are constant. The administration is also the same – all test takers get the same instructions, have the same length of time to work, and take the test under similar conditions of lighting, noise and temperature. Because the tests are standardised, they provide information about candidates that is comparable for all applicants.

Intelligence Tests:

These are tests to measure one’s intellect or qualities of understanding. They are referred to as tests of mental ability. The traits of intelligence measured include:

“reasoning, verbal and non-verbal fluency, comprehension, numerical, memory and spatial relations ability.”

Binet-Simon, Stanford-Binet and Weshler-Bellevue are some of the intelligence tests. Such tests are used for admission to MBA programmes, recruitment in Banks and other applications. The major criticism against these tests are that they to discriminate against rural people and minorities. Also, since most of these tests are administered in English the results may be influenced by one’s command over language rather than one’s intelligence.

Aptitude Tests:

Aptitude refers to one’s natural propensity or talent or ability to acquire a particular skill. While intelligence is a general trait, aptitude refers to a more specific capacity or potential. It could relate to mechanical dexterity, clerical, linguistic, musical academic etc. Most aptitude tests are standardised that they are not specific to any particular job. But they are general enough to be used in different job situations. OTIS Employment Test, Wesman Personal Classification Test are examples of general aptitude tests. Certain types of aptitude tests called psychomotor tests measure hand and eye co-ordination and manipulative skills. The MacQuarrie Test for Mechanical Ability and the O’connor Finger and Tweezer Dexterity Tests are examples of psychomotor tests. There are other types of aptitude tests to measure personal (how to decide for themselves appropriately in time) and interpersonal (social relations) competence.

Achievement Tests:

These are proficiency tests to measure one’s skill or acquired knowledge. The paper and pencil tests seek to test a person’s knowledge about a particular subject. But there is no guarantee that a person who knows most also performs the best. Work sample tests or performance tests using actual task and working conditions (than simulated one’s) provide standardised measures of behaviour to assess the ability to know. Work sample tests are most appropriate for testing abilities in such skills as typing, stenography and technical trades. Work sample tests bear relationship between test content and job content and job performance.

PIP Tests:

PIP tests are those which measure one’s personality, interests and preferences. These tests are designed to understand the relationship between any one of these and certain jobs.

Tests of one’s personality traits or characteristics are sometimes referred to as personality inventories. These tests help to measure characteristics such as maturity, sociability, objectivity etc. Unlike tests, inventories do not have right or wrong answers. Personality inventories help in selection decisions and are used for associating certain traits with sales persons and certain others with R&D personnel. Minnesota Multiphase Personality Inventory and California Psychological Inventory are examples of Personality Inventories.

Interest tests are inventories of likes and dislikes of people towards occupations, hobbies etc. These tests help indicate which occupations are more in tune with a person’s interests.

Strong Vocational Blank and Kuder Preference Records are examples of interest tests. These tests do not help in predicting on the job performance

Preference Tests try to match employee preferences with job and organisational characteristics. Hackman and Oldham’s Job Diagnostic Survey is an example of a preference test.

Projective Tests:

These expect the candidates to interpret problems or situations. Response to stimuli will be based on the individual’s values, beliefs and motives.

Thematic Apperception Test and Rorschach Ink Blot Test are examples of projective tests. In thematic Apperception Test a photograph is shown to the candidate who is then asked to interpret it. The test administrator will draw inferences about the candidate’s values, beliefs and motives from an analysis of such interpretation. The main criticisms against such tests are that they could be unscientific and reveal the personality of the test designer / administrator more than the applicant.

Other Tests:

A wide variety of other tests are also used. They are polygraph, graphology (handwriting analysis), non-verbal communication tests (gestures, body movement, eye contact etc.) and lie-detector tests.

In conclusion one should remember:

a. tests are to be used as a screening device.

b. tests scores are not precise measures. Tests can be used as supplements.

c. Norms have to be developed for each test, their validity and reliability for a given purpose is to be established before they are used.

d. Tests are better at predicting failure than success.

e. Tests should be designed, administered, assessed and interpreted only by trained and competent persons.

Most organisations use more than one selection device to gather information about applicants. Often these devices are used sequentially, in a multiple-hurdle decision-making scheme (candidates must do well on an earlier selection device to remain in the running and to be assessed by later devices).

Application Blank Reject Some Candidates

Screening Interview Reject Some Candidates

Tests Reject Some Candidates

More Interviews Reject Some Candidates

Reference Checks Reject Some Candidates

Conditional Offers Reject Some Candidates

Physical Examination

Hire

Often HR department takes the responsibility for the first few hurdles of assessing application blanks, conducting brief screening interviews, and administering ability tests. Then one or more managers / supervisors interview the survivors of these hurdles. Finally pending satisfactory reference checks, offers are made, medical examinations are completed and hiring is finalised.

Application Blanks and BIODATA: Application blank and / or resume is the first selection hurdle for most jobs. Application blanks request information about education, history and skills, as well as names and addressees of the applicant and several references. Most of the information requested is factual and can be verified, such as degrees earned or dates of employment. Application blank or resume fraud is not uncommon. Some studies indicate that 20 to 50 percent of the candidates falsify or slightly inflate some of their credentials.15 Thus seeking confirmation of important credentials is a wise practice.

Most organisations use application blanks or resumes to screen out candidates who do not meet the minimum job specifications on education or experience. Beyond these basics, a manager or HR officer may informally evaluate the application to find the candidates who look most promising. The criteria applied in making this judgement may not be explicit, job-related or consistent from one screener to the next.

A second way that organisation can use an application blank data is to apply a weighing scheme, in which only items known to relate to job success are scored and utilised in decision making. Weighted application blank (WAB) procedures have been shown to produce scores that predict performance, tenure and employee theft. Because the weights are valid and are applied consistently to all applicants, this method of using application blank data is more reliable than the informal evaluation.

Using Biodata, Experience, and Accomplishment Records for Selection: Biodata is a term used to refer to any type of personal history, experience, or education information. Some organisations use a biographical -information questionnaire instead of or in addition to, the usual application blank. These biodata questionnaires may be much more detailed than application blanks, and may be scored with keys based on very sophisticated statistical analyses.16. Sample questions might include “Do you repair mechanical things in your home, such as appliances?” “As a child, did you collect stamps?” Or “How many times did your family move while you were growing up?” One such biodata question – “Did you ever build a model aeroplane that flew?” -- was almost as powerful a predictor of success in flight training during World War II as the entire U.S. Air Force battery of selection tests. 17

Experience an Accomplishments Records:

Rather than relying on informal methods of evaluating candidate’s training, job-experience, and accomplishments, some organisations use content-valid-job-experience questionnaires to screen candidates for technical and professional jobs. The usual procedure is to conduct a job analysis by the task inventory method, in order to identify the most the most important or time-consuming tasks. The results of this job analysis are turned in to questions about the past work experience with each task or with each type of equipment used.

Applicants answer each task question by selecting one of the following responses:

▪ I have never done this task

▪ I have done it under supervision

▪ I have done it on my own

▪ I have supervised and / or taught this task

To discourage inflated self-ratings, the questionnaire may ask the applicants to list the names and addresses of people who can verify their experience with each task.

In addition, some job-experience questionnaires contain a few plausible sounding but non-existent task statements (such as typing from audio-FORTRAN reports, operating matriculation machines). Applicants who claim to have performed these non-existent tasks may be exaggerating their experience with real tasks.

Tests:

A test is a means of obtaining a standardised sample of behaviour. Tests are standardised in content, scoring, and administration. That is every time a test is given, its questions are identical or, in the case of tests with more than one form, equivalent. The scoring rules are constant. The administration is also the same – all test takers get the same instructions, have the same length of time to work, and take the test under similar conditions of lighting, noise and temperature. Because the tests are standardised, they provide information about candidates that is comparable for all applicants.

Intelligence Tests:

These are tests to measure one’s intellect or qualities of understanding. They are referred to as tests of mental ability. The traits of intelligence measured include:

“reasoning, verbal and non-verbal fluency, comprehension, numerical, memory and spatial relations ability.”

Binet-Simon, Stanford-Binet and Weshler-Bellevue are some of the intelligence tests. Such tests are used for admission to MBA programmes, recruitment in Banks and other applications. The major criticism against these tests are that they to discriminate against rural people and minorities. Also, since most of these tests are administered in English the results may be influenced by one’s command over language rather than one’s intelligence.

Aptitude Tests:

Aptitude refers to one’s natural propensity or talent or ability to acquire a particular skill. While intelligence is a general trait, aptitude refers to a more specific capacity or potential. It could relate to mechanical dexterity, clerical, linguistic, musical academic etc. Most aptitude tests are standardised that they are not specific to any particular job. But they are general enough to be used in different job situations. OTIS Employment Test, Wesman Personal Classification Test are examples of general aptitude tests. Certain types of aptitude tests called psychomotor tests measure hand and eye co-ordination and manipulative skills. The MacQuarrie Test for Mechanical Ability and the O’connor Finger and Tweezer Dexterity Tests are examples of psychomotor tests. There are other types of aptitude tests to measure personal (how to decide for themselves appropriately in time) and interpersonal (social relations) competence.

Achievement Tests:

These are proficiency tests to measure one’s skill or acquired knowledge. The paper and pencil tests seek to test a person’s knowledge about a particular subject. But there is no guarantee that a person who knows most also performs the best. Work sample tests or performance tests using actual task and working conditions (than simulated one’s) provide standardised measures of behaviour to assess the ability to know. Work sample tests are most appropriate for testing abilities in such skills as typing, stenography and technical trades. Work sample tests bear relationship between test content and job content and job performance.

PIP Tests:

PIP tests are those which measure one’s personality, interests and preferences. These tests are designed to understand the relationship between any one of these and certain jobs.

Tests of one’s personality traits or characteristics are sometimes referred to as personality inventories. These tests help to measure characteristics such as maturity, sociability, objectivity etc. Unlike tests, inventories do not have right or wrong answers. Personality inventories help in selection decisions and are used for associating certain traits with sales persons and certain others with R&D personnel. Minnesota Multiphase Personality Inventory and California Psychological Inventory are examples of Personality Inventories.

Interest tests are inventories of likes and dislikes of people towards occupations, hobbies etc. These tests help indicate which occupations are more in tune with a person’s interests.

Strong Vocational Blank and Kuder Preference Records are examples of interest tests. These tests do not help in predicting on the job performance

Preference Tests try to match employee preferences with job and organisational characteristics. Hackman and Oldham’s Job Diagnostic Survey is an example of a preference test.

Projective Tests:

These expect the candidates to interpret problems or situations. Response to stimuli will be based on the individual’s values, beliefs and motives.

Thematic Apperception Test and Rorschach Ink Blot Test are examples of projective tests. In thematic Apperception Test a photograph is shown to the candidate who is then asked to interpret it. The test administrator will draw inferences about the candidate’s values, beliefs and motives from an analysis of such interpretation. The main criticisms against such tests are that they could be unscientific and reveal the personality of the test designer / administrator more than the applicant.

Other Tests:

A wide variety of other tests are also used. They are polygraph, graphology (handwriting analysis), non-verbal communication tests (gestures, body movement, eye contact etc.) and lie-detector tests.

In conclusion one should remember:

a. tests are to be used as a screening device.

b. tests scores are not precise measures. Tests can be used as supplements.

c. Norms have to be developed for each test, their validity and reliability for a given purpose is to be established before they are used.

d. Tests are better at predicting failure than success.

e. Tests should be designed, administered, assessed and interpreted only by trained and competent persons.

INTERVIEW:

Virtually all organisations use interviews as a selection device for most jobs. Generally candidates are interviewed by at least two people before being offered a job. HR specialist and the person who will be the candidate’s immediate supervisor conduct these interviews. For managerial and professional jobs, it is common for the candidate to have a third interview with a higher level manager, such as a division head. Because the interview is so popular, one might think it is a highly useful election device. But this is not always the case. We shall consider the reliability and validity of the interview.

Reliability of the Interview:

In the interview context, reliability is consensus, or agreement, between two interviewers on their assessment of the same candidates. This is called Interrater Reliability. Research shows that it is rather weak.

Validity of the Interview:

The predictive validity of the interview is very low. Research in 1970s and 1980s suggested that the average validity of the interview for predicting job performance was as low as 0.14. 20 However, recent research has suggested that some individual interviewers may be valid, whereas many others are not. Past research has also lumped various types of interview procedures together, but very recent research suggests that some interview procedures can be quite valid.21

What can go wrong in the typical interview to cause many interviewers to make inaccurate predictions? It seems that interviewers often commit judgmental and perceptual errors that can compromise the validity of their assessments.

Similarity Error: Interviewers are positively predisposed to candidates who are similar to them (in hobbies, interests, personal background). They are negatively disposed to candidates who are unlike them.

Contrast Error: When several candidates are interviewed in succession, raters tend to compare each candidate with the preceding candidates instead of an absolute standard. Thus an average candidate can be rated as higher than average if he or she comes after one or two poor candidates and lower than average if he or she follows an excellent candidate.

First Impression Error: Some interviewers tend to form a first impression of candidates rather quickly, based on a review of the application blank or on the first few moments of the interview. Thus, this impression is based on relatively little information about the candidate. Nevertheless the initial judgement is resistant t change as more information or contradictory information is acquired. In addition, the interviewer may choose subsequent questions based on the first impression, in an attempt to confirm the positive or negative impression.

Traits Rated and Halo Error: Halo error occurs when either the interviewer’s overall impression or strong impression of a single dimension spreads to influence his or her rating of other characteristics. For instance, if a candidate impresses the interviewer as being very enthusiastic, the interviewer might tend to rate he candidate high on other characteristics, such as job knowledge, loyalty and dependability. This is especially likely to happen when the interviewer is asked to rate many traits

Types of Interviews

Virtually all organisations use interviews as a selection device for most jobs. Generally candidates are interviewed by at least two people before being offered a job. HR specialist and the person who will be the candidate’s immediate supervisor conduct these interviews. For managerial and professional jobs, it is common for the candidate to have a third interview with a higher level manager, such as a division head. Because the interview is so popular, one might think it is a highly useful election device. But this is not always the case. We shall consider the reliability and validity of the interview.

Reliability of the Interview:

In the interview context, reliability is consensus, or agreement, between two interviewers on their assessment of the same candidates. This is called Interrater Reliability. Research shows that it is rather weak.

Validity of the Interview:

The predictive validity of the interview is very low. Research in 1970s and 1980s suggested that the average validity of the interview for predicting job performance was as low as 0.14. 20 However, recent research has suggested that some individual interviewers may be valid, whereas many others are not. Past research has also lumped various types of interview procedures together, but very recent research suggests that some interview procedures can be quite valid.21

What can go wrong in the typical interview to cause many interviewers to make inaccurate predictions? It seems that interviewers often commit judgmental and perceptual errors that can compromise the validity of their assessments.

Similarity Error: Interviewers are positively predisposed to candidates who are similar to them (in hobbies, interests, personal background). They are negatively disposed to candidates who are unlike them.

Contrast Error: When several candidates are interviewed in succession, raters tend to compare each candidate with the preceding candidates instead of an absolute standard. Thus an average candidate can be rated as higher than average if he or she comes after one or two poor candidates and lower than average if he or she follows an excellent candidate.

First Impression Error: Some interviewers tend to form a first impression of candidates rather quickly, based on a review of the application blank or on the first few moments of the interview. Thus, this impression is based on relatively little information about the candidate. Nevertheless the initial judgement is resistant t change as more information or contradictory information is acquired. In addition, the interviewer may choose subsequent questions based on the first impression, in an attempt to confirm the positive or negative impression.

Traits Rated and Halo Error: Halo error occurs when either the interviewer’s overall impression or strong impression of a single dimension spreads to influence his or her rating of other characteristics. For instance, if a candidate impresses the interviewer as being very enthusiastic, the interviewer might tend to rate he candidate high on other characteristics, such as job knowledge, loyalty and dependability. This is especially likely to happen when the interviewer is asked to rate many traits

Types of Interviews

Interviews can be classified by their degree of structure, or the extent to which interviewer plan the questions in advance and ask the same questions of all the candidates for the job. Three types of interviews, based on three degrees of structure, can be defined:

Unstructured Semistructured Structured (interviews)

Unstructured Interviews:

Here questions are not planned in advance, and interviews with different candidates may cover quite different areas of past history, attitudes, or future plans. They have low interrator reliability and lowest validity. Because questions are not planned, important job related areas may remain unexplored, and illegal questions may be asked on the spur of the moment.

Semistructured Interviews:

Involves some planning on the part of the interviewer but also allows flexibility in precisely what the interviewer asks the candidates. Semistructured interviews are likely to be more valid than unstructured ones, but not as valid as highly structured interviews.

Structured Interviews:

Research shows conclusively that the highest reliability and validity are realised in the structured interview. In a structured interview, questions are planned in advance and are asked of each candidate in the same way. The only difference between interviews with different candidates might be in the probes, or follow-up questions, if a given candidate has not answered the question fully. Interviews that feature structured questions usually also provide structured rating scales on which to evaluate the applicants after the interview.

Stress Interview:

Sometimes where the job requires the jobholder to remain calm and composed under pressure, the candidates are intentionally subjected to stresses and strains in the interview by asking some annoying or embarrassing questions. This type of interview is called stress interview.

Placement:

Placement refers to assigning rank and responsibility to an individual, identifying him with a particular job. If the person adjusts to the job and continues to perform per expectations, it means that the candidate is properly placed. However, if the candidate is seen to have problems in adjusting himself to the job, the supervisor must find out whether the person is properly placed as per the latter’s aptitude and potential. Usually, placement problems arise out of wrong selection or improper placement or both. Therefore, organisations need to constantly review cases of employees below expectations / potential and employee related problems such as turnover, absenteeism, accidents etc., and assess how far they are related to inappropriate placement decisions and remedy the situation without delay.

Induction:

Induction refers to the introduction of a person to the job and the organisation. The purpose is to make the employee feel at home and develop a sense of pride in the organisation and commitment to the job.

The induction process is also envisaged to indoctrinate, orient, acclimatise, acculture the person to the job and the organisation.

The basic thrust of Induction training during the first one or few weeks after a person joins service in the organisation is to:

▪ Introduce the person to the people with whom he works,

▪ Make him aware of the general company policies that apply to him as also the specific work situation and requirements,

▪Answer any questions and clarify any doubts that the person may have about the job and the organisation;

▪ provide on-the-job instructions, check back periodically how the person is doing and offer help, if required.

While The HR staff may provide general orientation relating to the organisation, the immediate supervisor should take the responsibility for specific orientation relating to the job and work-unit members. The follow-up of orientation is to be co-ordinated by both the HR department and the supervisor with a view mainly to obtain feedback and provide guidance and counselling as required.

Proper induction would enable the employee to get off to a good start and to develop his overall effectiveness on the job and enhance his potential.

Unstructured Semistructured Structured (interviews)

Unstructured Interviews:

Here questions are not planned in advance, and interviews with different candidates may cover quite different areas of past history, attitudes, or future plans. They have low interrator reliability and lowest validity. Because questions are not planned, important job related areas may remain unexplored, and illegal questions may be asked on the spur of the moment.

Semistructured Interviews:

Involves some planning on the part of the interviewer but also allows flexibility in precisely what the interviewer asks the candidates. Semistructured interviews are likely to be more valid than unstructured ones, but not as valid as highly structured interviews.

Structured Interviews:

Research shows conclusively that the highest reliability and validity are realised in the structured interview. In a structured interview, questions are planned in advance and are asked of each candidate in the same way. The only difference between interviews with different candidates might be in the probes, or follow-up questions, if a given candidate has not answered the question fully. Interviews that feature structured questions usually also provide structured rating scales on which to evaluate the applicants after the interview.

Stress Interview:

Sometimes where the job requires the jobholder to remain calm and composed under pressure, the candidates are intentionally subjected to stresses and strains in the interview by asking some annoying or embarrassing questions. This type of interview is called stress interview.

Placement:

Placement refers to assigning rank and responsibility to an individual, identifying him with a particular job. If the person adjusts to the job and continues to perform per expectations, it means that the candidate is properly placed. However, if the candidate is seen to have problems in adjusting himself to the job, the supervisor must find out whether the person is properly placed as per the latter’s aptitude and potential. Usually, placement problems arise out of wrong selection or improper placement or both. Therefore, organisations need to constantly review cases of employees below expectations / potential and employee related problems such as turnover, absenteeism, accidents etc., and assess how far they are related to inappropriate placement decisions and remedy the situation without delay.

Induction:

Induction refers to the introduction of a person to the job and the organisation. The purpose is to make the employee feel at home and develop a sense of pride in the organisation and commitment to the job.

The induction process is also envisaged to indoctrinate, orient, acclimatise, acculture the person to the job and the organisation.

The basic thrust of Induction training during the first one or few weeks after a person joins service in the organisation is to:

▪ Introduce the person to the people with whom he works,

▪ Make him aware of the general company policies that apply to him as also the specific work situation and requirements,

▪Answer any questions and clarify any doubts that the person may have about the job and the organisation;

▪ provide on-the-job instructions, check back periodically how the person is doing and offer help, if required.

While The HR staff may provide general orientation relating to the organisation, the immediate supervisor should take the responsibility for specific orientation relating to the job and work-unit members. The follow-up of orientation is to be co-ordinated by both the HR department and the supervisor with a view mainly to obtain feedback and provide guidance and counselling as required.

Proper induction would enable the employee to get off to a good start and to develop his overall effectiveness on the job and enhance his potential.